Plenary lecture, conference Communication in the Multilingual City, Birmingham, 28-29 March 2018.

Jan Blommaert

In today’s multilingual city, a lot of communication is done in online environments. In fact, even in places that do not, perhaps, see themselves as multilingual, it is online communication that makes them multilingual (as much of the work on rural provinces in The Netherlands performed by my good Tilburg colleague Jos Swanenberg has demonstrated). The argument is not new, I know, and it has been reiterated at this conference as well. But let me nonetheless repeat it, for it underlies what follows: contemporary sociolinguistic environments are defined by the online-offline nexus, and this propels us towards two analytical directions: complexity and multimodality. I shall engage with both in this talk.

My engagement with these phenomena has pushed me, of late, to reflect on a very broad social-theoretical topic. That topic is: “what are groups”? Who actually lives in these multilingual cities?, and how do people whose social lives are continually dispersed over offline and online context arrive at forms of collective action?

Note that the question “what are groups” has been a recurrent one in social thought throughout the past century and a half. It always accompanies major technological and infrastructural transformations of societies: the breakthrough and spread of printed newspapers, the telegraph, cinema, telephone, television kept Weber, Durkheim and Simmel busy, as well as the Frankfurt School, Dewey, Lippman and later Giddens, Habermas, Bourdieu and Castells. New technologies each time called into question the very nature of what it meant to be social. That is: what it meant to form communities and collective action, using instruments not previously available. The question “what are groups” is, thus, inevitable when we consider the online-offline nexus that characterizes our societies at present.

In addressing the question, I take my cues from Garfinkel and other Symbolic Interactionists (including the Goodwins, I must underscore), for reasons that will be made clear in due course. Let me say at this point that contemporary social and sociolinguistic complexity creates a serious degree of unpredictability, in that we cannot presuppose, let alone take for granted, much of what mainstream social theory has offered us to conceptualize communities, identities and social life. What Garfinkel offers is a rigorous, even radical, action-focused perspective on society, in which groups are seen as EFFECTS of specific forms of social interactions.

EFFECTS, not GIVENS that determine and define the interactions. I underscore this for it isn’t what we normally do: we tend to take groups and group identities as pre-given when we consider interaction, and then observe what such groups and identities “do” in interaction. For Garfinkel this is not an option. He argues that social collectives are the product of collective social action – which is always interaction of course. And when is such action collective? When the activities deployed by participants are RECOGNIZABLE to others in terms of available cultural material. It is as soon as we recognize someone else’s actions as meaningful in terms of available (and thus recognizable) resources for meaning, that we engage in collective social action, display and enact the formats we know as characterizing the specific social relationships possibly at play, and operate as a group.

In the online space, we have no access to the embodied cues that offer us pointers to the interloctors’ identities in offline talk, but we can still observe social interaction and the ways in which it points us to groups. Groups cannot be an a priori, but they can be an a posteriori of analysis.

Methodologically, this is how I reformulate Garfinkel’s focus on action. I use a very simple, four-line set of principles. ONE: whenever we see forms of communication we can safely assume that they involve meaningful social relationships as prerequisite, conduit and outcome. TWO, such relationships will involve modes of identity categorization. THREE, observing modes of interaction, thus, brings us at the very hard of what it is to be social. And FOUR, we must be specific and avoid quick generalizations, for differences in action will lead to different outcomes.

In what follows, I will take these simple principles to a typical online phenomenon: memic hasthtag activism. Memic hashtag activism has become, rather quickly in fact, a major new format of political activism, certainly where Twitter is concerned. And even if it is by definition an online form of action mobilizing the now-typical online multimodal resources for interaction, there are clear offline effects too.

The particular case I have chosen here is Dutch, and it revolves around the former Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, mister Halbe Zijlstra. Let us quickly provide some general informative points.

Zijlstra was until very recently a rising star in Dutch politics, climbing fast through the ranks of the ruling liberal party VVD due to a very close relationship with Prime Minister Rutte. When the most recent Dutch government was formed, Zijlstra got the plum job of Minister of Foreign Affairs. So far so good.

Now, Halbe Zijlstra had for years been telling a story. The story was that, in a pre-political capacity, he was present at a party at Vladimir Putin’s datcha, where he overheard Putin saying that Ukraine, Georgia and other former Soviet stations should become part of a future Greater Russia. He had heard Putin saying something that could, in other words, be an indication of Russian imperialist ambitions.

In February 2018, while Zijlstra was preparing to meet his Russian counterpart Lavrov, a newspaper reported that all of this was a lie. Now, you must know that the relations between The Netherlands and Russia are delicate due to the incident with a Malaysian airliner shot down in 2014 over the Russian-occupied part of Ukraine, killing 193 Dutch nationals. Zijlstra’s talks with Lavrov were announced to be tough, and just as that was about to happen, Halbe Zijlstra’s credibility got shot to pieces.

There were two problems. ONE, it was shown that Zijlstra was never present at that party. A top executive of oil company Shell was there, and Zijlstra had heard the account second hand, from him. The SECOND problem, however, was that this Shell guy came out saying that Putin had actually argued something else: Ukraine, Georgia and so on were past of Greater Russia’s past, not its future. Halbe Zijlstra, in short, had been caught “pants down”, lying quite nastily about the people he now had to do business with.

Social media went bananas, and on Twitter a meme-storm started, which lasted for 24 hours and operated under the hashtag #HalbeWasErbij – in English “Halbe was there”. A hashtag, by the way, is a framing device that ties large numbers of individual messages thematically, pragmatically and metapragmatically together within a common broad indexical vector. And in this function, it is of course an online innovation.

Let’s now have a look at the meme-storm.

Obviously, Halbe’s claim that he WAS THERE with Putin became a meme theme. Hilarious parodies of this theme, preposterously suggesting intimacy between both, started circulating. Zijlstra was with Putin on a trip into the woods.

His photo dominates the Kremlin.

And Putin supports Zijlstra in the Dutch Parliament.

Those are straightforward memes, even to some extent logical and expected permutations of Zijlstra’s claims. But “Halbe Was There” can of course be made more productive as a motif. And this is what happens in meme-storms: the productivity of the theme is exploited, leading to ever more absurd extensions of “Halbe Was There”.

Halbe was there when Napoleon marched his victorious troops through Europe.

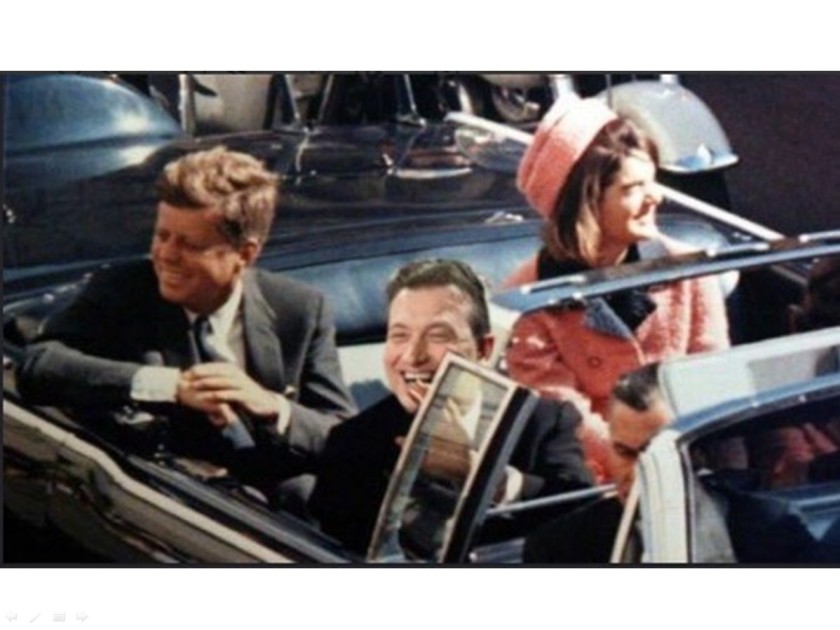

He was in Dallas in 1963

He was there when Martin Luther King had his dream.

There cannot be any doubt that Halbe was one of the Beatles.

Whenever history was made, Halbe was there. So when Charles and Diana got married, guess who stood next to them.

And since this guy is now the biggest maker of history, he too must be connected to Halbe.

The meme-storm went on, relentlessly, for hours on end. And in this new information economy of ours, new and old media do not operate in entirely separate spaces but are profoundly networked. So what is “trending” on Twitter tends to become headline news in the traditional mass media too.

Such a scale jump from small levels of new media circulation to larger mass media ones generates a tremendous impact. Soon, the Dutch national broadcasting system made an item of the #HalbeWasErbij phenomenon, substantially adding to the public pressure on Zijlstra by complementing more strictly political arguments against him with ludic ones ridiculing him, entirely undercutting his credibility and, consequently, his political reliability.

And so, by the time Halbe Zijlstra was forced to resignation about a day after the start of the meme-storm, this was world news. Memic hasthtag activism is effective because of the impact it has on mass media.

This impact has not necessarily to do with the masses carrying so-called “public opinion”. I mentioned “trending” here. Now, usually when we say “trending” we imply “viral”. And “viral”, in turn, is somehow strongly associated with large numbers. (Think of Trumps tweets which get hundreds of thousands of “likes” and retweets.)

In this case, however, “viral” is in actual fact “LOW VIRALITY”. Consider the images on this slide. On the left, we see the most popular meme of the entire meme-storm. Yes, it received almost 900 retweets, but compared to the heavy artillery of, for instance, Trump, Taylor Swift, or your average Premier League star, this is peanuts. The virality in the #HalbeWasErbij in effect amounted to a handful to a few dozen of retweets. That’s strange, isn’t it?

Unless we consider the kind of community behind it. This community is, whenever we count heads, small. But it is relentless and profoundly committed to what it practices. The memes were used as instruments in dialogue, in the form of ludic replies to wordy statements as well as to other memes – causing genre shifts in Twitter threads from one type of debate format into another one. And above all, what we saw was unending creativity, with continuous transformations of memes in a kind of saturation bombardment on the topic of Zijlstra’s politically consequential lies.

And the latter point is very interesting, for what characterizes memic hashtag activism is that it occurs not necessarily on the basis of a pre-existing community of experienced activists, but in an ephemeral, open, “light” community tied together by a set of formatted practices. I mean by that: the idea is to make more memes and new ones, and anyone joining the community is welcome as long as he or she steps into this format.

It’s an easy and cheap format in addition. The skills needed are widely available – you just need inspiration and some photoshopping technique, and you will have the time of your life. And for those who lack the photoshopping skills, other members step in. At one point during the afternoon, someone tweeted this image:

This is a photoshopped section of this picture, where we see Halbe Zijlstra athletically jumping over a fence.

And the photoshopped section is offered, in a sort of ludic instruction mode, as raw material to people lacking some necessary skills but desiring to enter into the #HalbeWasErbij meming activities.

Now, this actual, slightly awkward pose of Zijlstra’s became the most popular one in the meme-storm.

Dallas, 1963

Normandy 1944

Berlin 1989: Halbe Was There, each and every time, in this photoshopped capacity.

He was even there when Leonardo painted La Gioconda. And of course, Halbe was on the pitch when Holland had its finest moment:

When they won the European Cup in 1988: Yes sir, Halbe Was There.

We can conclude now.

It is through paying attention to what people DO that we can get to what and who they ARE – this is what Garfinkel and his associates emphasized.

We have seen how the hashtag #HalbeWasErbij connected a very large set of transformed, morphed, memes in what Anselm Strauss famously called “the continual permutation of action”. This continual permutation is the core of interaction here: we see on this slide how three different memes refer to the same moment in history, a World Cup game between Spain and Holland, which Holland won. Those involved in the meming activities interact through small but profoundly creative and ludic transformations of particular signs, all of them connected and all of them separate. Those involved in it are form a loose, rhizomatic community without fixed boundaries, but with – surprisingly perhaps – a pretty robust structure revolving around shared expectations, shared cultural material and shared norms of engagement. It’s all about learning, showing, trying, sharing, and having politically informed good laughs. And it proceeds within the constraints of what Twitter affords (the so-called platform affordances) as well as within the boundaries of what is recognizable in terms of the formats of action.

This explains the “low virality” issue: not MEMES go viral, but MEMING as an activity goes viral and shapes a viral community (another term for “rhizomatic”, perhaps). We can say here that “virality” is not a quantitative matter, but a qualitative one that has to do with the intensity of interaction within particular formats of social action. This interaction, we have seen, is characterized by tremendous variability, yet it is tied together by a hashtag, which gives it a specific INDEXICAL VECTOR: any and all individual tokens of the hashtag point towards the same thematic complex, connect a community in the activity, and shape networks of communicability to other actors in the field of the shaping of public opinion. The national broadcasting system in The Netherlands, let alone Reuters, has a much wider audience than the individual hashtag activists. But the latter’s relentlessness and intensity became the stuff of higher-scale political expression by so-called “influencers” and mass media.

This evidently complicates our understanding of “public opinion”. We see that small and “light” but nonetheless structured communities can, through networked upscaling effects, become tremendously influential in the public sphere. Those involved in various forms of local urban activism are doubtlessly already familiar with such unexpected high-scale effects of small-scale action. Such effects shape forces of collective meaning-making and understanding in our societies, in ways that we still largely need to find out. But while doing so I would propose to start from action, not from groups. Because as I hope to have demonstrated here, the effects of the actions cannot be predicted from the features of pre-existing groups, however we wish to imagine them.

![]()