Jan Blommaert

The problem

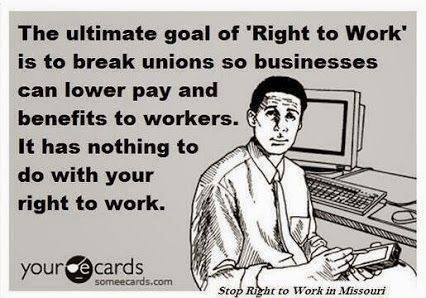

In a stimulating paper published in 2014, Ryuko Kubota expresses her concern about what she calls the “multi/plural turn” in the study of multilingualism (within Applied Linguistics, note), and cautions scholars “celebrating” multi-, plural- or metrolingualism for entering a high-risk zone: that of “complicity” with neoliberalism.

However, as this ‘turn’ grows in popularity, it seems as though its critical impetus has faded and its knowledge is becoming another canon—a canon which is integrated into a neoliberal capitalist academic culture of incessant knowledge production and competition for economic and symbolic capital, and neoliberal multiculturalism that celebrates individual cosmopolitanism and plurilingualism for socioeconomic mobility. (Kubota 2014: 2)

Kubota appears to be highly skeptical of work addressing contemporary forms of multilingualism and multiliteracies from the perspective of complexity. Such work, she suggests without much elaborate argument (or definition), is “postmodern”, and postmodernity, ostensibly, is to be approached with extreme caution, for it appears to render a critique of fundamental (“real-world”) inequalities and hegemonic pressure very difficult, if not impossible:

Although metrolingualism problematizes hybridity as superficial celebration, it is still grounded in the postmodern affirmation of multiplicity and fluidity, which keeps it from critiquing how inequality is often solidified or intensified within multiplicity and fluidity. (Kubota 2014: 4)

And this, then, risks enlarging and deepening the gulf between “theory and practice” in Applied Linguistics. “Postmodern” approaches are “theoretical”, they “celebrate” hybridity, fluidity, flexibility in language-and-identity work, and thus overlook the harsh realities of, for instance, the struggles of indigenous people to retain their endangered native languages – one case of “real world” hegemonic pressure – and the global dominance of English – another such instance.

Since I share many of Kubota’s “real world” concerns (she favorably cites some of my work on African asylum applicants), I intend to assist her in this mission. I shall do this from the specific viewpoint of sociolinguistic superdiversity (henceforth SSD; cf. Arnaut et al. 2016; Blommaert 2013).[1] The reason for that is that much of the work on SSD might be vulnerable to Kubota’s critique since such work would pay attention to complex forms of spoken and written code-mixing called “languaging”, and would emphasize mobility, flexibility, instability and fragmentation in most of its outcomes. I will structure my attempt around three theoretical assumptions in Kubota’s argument, which invite a critical scrutiny precisely from the viewpoint of SSD. Kubota, we shall see, opts for traditional, static and hence anachronistic versions of such assumptions. When reformulated from an SSD perspective, some of her fears can, one hopes, be alleviated. The first point conditions (and will clarify) the two subsequent ones.

Note, for clarity’s sake, that I do not necessarily endorse all the work currently being done under the label of sociolinguistic superdiversity (nor, more broadly, that done within the “multi/plural” trend identified by Kubota – because, yes, there is work that foolishly presents new forms of diversity as an unqualified good news show). But I can speak for myself and have the luxury of drawing on the efforts we collectively undertake within the INCOLAS framework.[2] And it is good to remind readers of what it is we do in such work. We describe contemporary sociolinguistic phenomena and patterns, in an attempt to arrive at an accurate and realistic ontology for contemporary sociolinguistic analysis – what are the objects of analysis exactly? And from such descriptions, we try to distill the theoretical generalizations that they afford. To the extent that we produce “theory”, therefore, our theory is a descriptive theory, not a normative one or a predictive one. And we do all of this (a) drawing on a broad range of inspiring work in macro-sociolinguistics, interactional sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology, linguistic ethnography, discourse analysis, literacy and multimodality studies, new media studies, sociology, critical theory and cultural studies; and (b) with a very strong preference for “applied” sites of research in which the big issues of contemporary social struggle are played: education, immigration, the labor market, popular (online) culture and information economies, policing and surveillance. The essays in Arnaut et al (2016) can serve as a sample of our approach, the series of working papers we edit offer a wider panorama.

Ideology

The concept of ideology utilized by Kubota in her paper is the “political ideology” one – where “ideology” stands for things such as neoliberalism, capitalism, Marxism and so forth and is closely connected with institutions and centers of power.[3] Thus, when she points towards the “ideological” effects of certain kinds of academic work, such effects could be “complicity with neoliberalism”, for instance. As in “the problematic ideological overlap between the multi/plural turn and neoliberal multiculturalism” (Kubota 2014: 2). She adopts, one could say, the version of “ideology” widespread in Critical Discourse Analysis: something that does not operate in language-in-society, but on language-in-society, as an external force operating hierarchically through institutional power.

She seems to find little value in (or at least: has not used) the work on language ideologies – perhaps the most momentous theoretical intervention in the study of language and society of the past decades (e.g. Silverstein & Urban 1996; Kroskrity et al. 1998; Kroskrity 2000; Agha 2007). Kubota does mention the “standard language ideology”, but not in a language-ideological analytical sense: this phrase refers to a top-down institutional hegemony, to an institutionally enforced normative and prescriptive “regime of language” in other words. This is a great pity, for one of the crucial effects of language ideology research is that it has shaped a new sociolinguistic ontology. “Language” – that clumsy modernist notion – can now be seen as a “laminated” object consisting of practices joined, organized and structured by beliefs about practices – pragmatics and metapragmatics always operate in conjunction whenever people produce and exchange bits of “language”. The term “standard language ideology”, in language-ideological terms, would stand for the socially ratified belief that specific forms of language are “standard” forms and thus better than other “nonstandard” forms (cf. Silverstein 1996), not for the prescriptive institutional normativity imposed, for instance, on school systems, public administrations or law courts. Such language ideologies – take the “standard language ideology”, exist and persist with a degree of detachment from observable sociolinguistic practices. A strictly enforced “standard language ideology” in schools, for instance, may be “adhered to” (and even vigorously defended) by teachers who, in actual fact, produce tremendous amounts of “substandard” speech in class.

The laminated object of language ideologies research enables us to see broad, and socio-politically highly significant, gaps between observable language behavior on the one hand, and beliefs about such behavior on the other hand. People very often act in outright contradiction with firmly held beliefs about such actions. This does not lead language ideology scholars to dismiss such language-ideological beliefs as “false consciousness”, i.e. wrong and therefore irrelevant beliefs: it is precisely the tension between such beliefs and the characteristics and patterns of actual activities that leads such scholarship to robust, critical and innovative statements on the relationships between language and social structure (Agha 2007).

Kubota writes, referring to some of my work:

Contrary to the postmodern sociolinguistic idea that language is no longer fixed at a certain location (…), claiming to belong to ancestral land constitutes important means for language preservation or revitalization and for resistance in indigenous communities. (Kubota 2014: 9)

In view of what was said above, I see no contradiction. I see two different objects: one, an empirically observable detachment of actually-used-language from locality (hard to deny when one considers, for instance, the global spread of different forms of “English” and new modes of online diasporic life); and another one referring to strongly held beliefs denying such forms of mobility. Both require attention and disciplined inquiry, for precisely the capacity for delocalization may contribute to successful struggles for “local” language revitalization. The fact that people are emphatic in claiming a unique local authenticity for their language does not, in no way, predict their actual patterns of language usage. In fact, nowadays such powerful claims are often made in English, and on the internet rather than in the village.

Failing to observe such distinctions, and take them seriously, obscures both the actual ways in which power operates, and the precise loci of such power. As for the former: a strongly stressed monoglot regime can, in actual fact, prove extraordinarily lenient and flexible when observed in practice (we very often see the curious balance between “orthodoxy” and “orthopraxy”, described by James Scott, with various forms of “hidden transcripts” emerging – Rampton 2006). As for the latter, I know that there is a strong tendency to see power regimes as “total”; but I know that in actual fact, even very “total” ones contain cracks and gaps – something we should have learned from Bakhtin and Voloshinov. This is not to minimize power, on the contrary: it is taking it absolutely serious by being absolutely precise and factual about it. No social cause is served by shoddy work, Dell Hymes famously said. I couldn’t agree more.

The dated and altogether extremely partial conceptualization of ideology by Kubota makes her overlook such crucial features of contemporary sociolinguistic economies, and closes lines of creative thinking about solutions for sociolinguistic inequality. One such line, we shall see, has to do with how we conceptualize “language”. To this I can presently turn.

Language

I have read – but forgot the locus – that I “deny the existence of language”. This would be a pretty disconcerting allegation for a scholar of language, were it not that I have a reasonable and reasoned answer to that. I do not deny or reject anything, I refute, usually on generously evidenced grounds, a particular conceptualization of language as a unified, countable and closed object. The “modernist” version of it, in short, that characterized the synchronicity of structuralism in its Lévi-Straussian varieties.[4] This modernist version of “language” is entirely inadequate for describing sociolinguistic phenomena and patterns as currently practiced by subjects in very large parts of the world. To my repeated surprise, I have seen prominent scholars in Applied Linguistics subscribing to precisely such modernist versions, particularly when they discuss the areas where such a version is least applicable: endangered languages and the global dominance of English. Kubota is one of them, even if she is at pains to argue the opposite.

In order to understand the problem, we must outline the SDD position – again largely influenced by the language ideologies insights discussed above. First, I must repeat what I said above: we must distinguish between two different ways of using the term “language”. One is Language with a capital L – the named objects of lay discourse such as “English”, “Chinese” or “Zulu” – which is real as an ideological artifact because people believe it exists. It exists as a belief system and has often been given an institutionalized reality. The second is language as observable social action – the specific forms people effectively use in communicative practice. These forms are infused with language-ideological beliefs, but, as we saw earlier, they can contradict such beliefs, and such contradictions are not necessarily noticed. People in practice use a wide variety of resources, some of which are conventionally (i.e. indexically) attributed to some “Language” (e.g. English) even if the connection between such resources and the codified, standardized form of that “Language” is highly questionable. To which “Language”, for instance, must we assign globally used emoticons?

Two, this means that when we focus on the second “language” – the actual practices – we notice that established labels – such as “English” etc. – become a burden. For what we see in actual communicative practices is that people produce ordered sets of resources (attributed, sometimes and not necessarily, to some Language) governed by specific social norms specifying “orderly” social behavior in a specific social space. Different resources will be used, for instance, by the same person when addressing his mother than when addressing his school teacher. And the highly specific and situated (but structured!) nature of such practices enables us to understand why the same resources can have an entirely different value and effect in different situations – take a Jamaican accent in English, negatively valued in the classroom, neutrally in the ethnically heterogeneous peer-group, and positively in the after-school Reggae club (Rampton 1995). We see, thus, registers in actions, not Languages (cf. Silverstein 2003; Agha 2007), and such registers operate chronotopically, in the sense that we see them being put to use in highly specific timespace configurations, with specific identity-and-meaning effects in each specific chronotope. Shifts from one chronotope into another involve massive reordering of norms, resources and effects – Goffman’s “footing shifts” on steroids, one could say.

Registers, as a descriptive and analytical concept of immense ethnographic accuracy, allow us to explain otherwise contradictory phenomena as structured, in the sense that different phenomena must be situated in different spheres of social life. Above, I quoted Kubota’s pointing towards an alleged contradiction related to my work. In her text, she elaborates that tension as follows:

Indeed, it is difficult to negotiate two opposing poles: political efforts to seek collective rights to identity and attempts to support indigenous youths who negotiate their hybrid identity. (…) Additionally, who proposes either hybridity or authentication as a goal to be sought on what grounds? (Kubota 2014: 10)

We can only speak of “opposing poles” when the totality of social life is imagined as one straight line, as a singular and homogeneous thing in which just one set of norms dominates. There is no opposition, of course, when one sees both options as belonging to entirely different spheres of social life – one a tightly organized and scripted community struggle for identity recognition often based on “invented traditions” of purity, heritage and authenticity; the other a small peer group encounter in which youngsters discuss hiphop, for instance. No choice is required – there is no “either-or” scheme – for what happens is that the same youngsters participate in the first activity between 10 and 12 in the morning, after which they leave the larger group and congregate around a sound system in some friend’s room. Bakhtinian heteroglossia with an interactional-sociolinguistic twist, one could say. Ethnographic accuracy (and sociological realism, I’d add here) solves what looks like an intricate political puzzle here.

Observe, at this point, three massively important things.

- One: I fail to see how such analyses could “celebrate [neoliberal] individualism”. I will elaborate this point below, but we can already see that whatever is observed here is entirely social and can only be understood as such. Referring to my earlier point about the precise loci of power: we will begin to understand where power actually operates oppressively, and where it can be liberating and enabling, when we accept that social life does not proceed along one simple set of rules and norms, but demands an awareness of several sets of norms, to be played out in highly diverse social fields, some of which will be institutionally highly policed (think of the classroom above), while others obey very different power actors (think of the Reggae club). Power is a polycentric social fact.

- Two, this also counts for the inevitable notion of “repertoire” – too often dismissed as the hallmark of individualism whenever it’s being used. Repertoires are always strictly unique, for they bespeak an individual’s life trajectory. But – see above – since such trajectories, whenever they involve communication are by definition social, we shall see that repertoires are structured in the sense of Bourdieu: repertoires reflect the specific social history lived by individuals, and both the “social” and the “historical” need to be taken into account. Whatever is in someone’s repertoire reflects norms valid in some social sphere, and such norms are both specific (not generic), and dynamic (not static). Which is why academics of the present generation – and I do suppose I can generalize here – are able to write on a computer keyboard, while a mere three decades ago this form of literacy was the specialized (and often exclusive) skill of departmental secretaries, “typists”, as they were sometimes called – people who could type, a thing most people couldn’t. It also explains why “typists” have all but disappeared as a niche in the labor market in large parts of the world.

- Three: it is precisely such a view – the SSD view, as I announced it – that deals a devastating blow to that scientific pillar of neoliberalism: methodological individualism, the theoretical assumption that every human process must in fine be explained from within purely individual means, capabilities, concerns and interests. Responding to one axiom with another axiom is not a refutation, so claiming that people are social beings does not constitute a rejection of methodological individualism. It is the analysis of the delicate and complex interplay of resources, norms and social niches that constitutes an empirical refutation of neoliberal scientific assumptions. In that sense, the SSD approach continues, and expands, the “savage naturalism” of which symbolic interactionist sociologists such as Blumer, Becker, Cicourel and Goffman were so often accused by their rational-choice opponents, and it does so with a more powerful theoretical and analytical toolkit.

We can now return to Kubota’s concerns. In the field of endangered languages, a register-and-repertoire view of what goes on may relieve some of the anxieties often voiced by activist researchers. For what we see is that members of such endangered language communities usually construct “multilingual” repertoires that are, in effect, heteroglossic: specific resources are allocated to specific social environments, in the ways described earlier. A “dominant” (or “imperialist”, for some) Language can be used for certain forms of business, while the heritage Language is used for others. The heritage Language is not “replaced”, strictly speaking, by the dominant one, but it is “shrunk” and reduced to highly specific (often ritualized) social environments where it can appear in often minimal forms (cf Moore 2013). As for English – the “killer language” in Phillipson’s two decades-old jargon – it moves in alongside the other parts of the repertoires, usually also as a “truncated” and functionally specialized register. For some people and in some contexts it will be experienced as oppressive and constraining, for others in other contexts it will be experienced as a liberating, creative resource enabling forms of identity development previously not available. One can debate whether the heritage language, in such a scenario, has lost “vitality” or has, sometimes, consolidated or even strengthened precisely the functions it can realistically serve in the (again: social and historically structured) lives of its community members. Let us not forget that Lévi-Strauss published Tristes Tropiques in 1955, and Georges Balandier l’Afrique ambigüe in 1957: social and historical processes of this kind are generic, not specific.

Am I now again minimizing power – the effect of colonialism, for instance, or of neoliberal capitalism? I don’t believe I am. I am pointing, precisely, to ways in which people can make the best of a bad job, maximizing the limited space of autonomy and agency they effectively have in a restrictive sociopolitical configuration. For those who believe that replacing coercion with “free choice” by the “people themselves” will result in fundamentally different sociolinguistic patterns may be disappointed: freedom of choice always plays in a tightly organized and structured field and often generates the same outcomes as coercion. At this point I vividly remember the heated and frustrated discussions in early post-Apartheid South Africa, when activist scholars began to realize that the African “mother tongues” were not all that popular with many of their “native speakers” who now had acquired the right to use them in education, but who wanted (more than anything else) to send their sons and daughters to university in Johannesburg or other major cities – and wanted (as well as “frreely chose”) “good English” for that.

The fact remains that under the conditions I specified, endangered languages do not “die”. This insight may be shocking to the more extremely activist scholars involved in these debates; I hope it provides perspective and hope to the more realistic ones, and to the communities looking for ways to retain their valuable heritage. For combining a firm and convinced position on heritage and authenticity with “negotiating hybrid identities” is not just possible: it is the best that can happen in any community. Framing such intricate processes – the stakes of which far transcend language alone – in the simple either-or schemes I quoted from Kubota’s paper creates a political cul-de-sac as well as a sociological absurdity, and extends the life of the anachronistic concept of language I discussed earlier.

Groups

The difference between the SSD viewpoint outlined here and Kubota’s conceptualizations of groups and identities should be predictable by now. Given the two previous points, Kubota sticks to highly traditional notions of groupness and related features – the last quote above sketched a paralyzing and mistaken opposition between collective “authentic” identities and hybrid ones, as if both are incompatible; and she adds:

(…) hybridity tends to be more focused on individual subject positions than on group identity. (Kubota 2014: 11)

We see methodological individualism cropping up here – subject positions can hardly be strictly “individual” when they are achieved through the eminently social fact of meaningful social interaction and would, thus, better be called intersubjective positions. And as for “group identities”, they appear to are confined to the usual suspects: language, ethnicity, class, gender, nationality. Furthermore, whatever is “individual”, in Kubota’s view, reeks of neoliberalism:

An ideal neoliberal subject is cosmopolitan. However, critics argue that cosmopolitanism reflects individualism and an elite worldview of people with wealth, mobility, and hybridity in global capitalism, while undermining the potentially positive role of the nation, which could provide opportunities for workers and other groups to form solidarity.(Kubota 2014: 14)

Thus – here is a three-step chain of assumptions – scholars who (i) describe hybridity will, in some way, (ii) describe something “individualistic”, and thus (iii) implicitly subscribe to a neoliberal elite view of the world. Taking my own preferred research subjects, asylum seekers and other disenfranchised migrants (Bauman’s “vagabonds”), I see two things that contradict this claim. First, such people are entirely “cosmopolitan” and replete with features of “hybridity” but not at all wealthy or privileged. And, secondly, for such people the nation-state is extraordinarily powerful (and threatening) as an institutional environment. The nation-state has been written off so often, but this write-off stands in an uneasy relationship with the available evidence.

To add a third small point to this: the cosmopolitan and hybrid character of the subjects I mention does not exclude intense practices of informal solidarity and conviviality (Blommaert 2013), and the nation-state is often an enemy in this – very little solidarity is provided by the EU nation-states to asylum seekers presently, for instance. These subjects are “ideal neoliberal subjects”, though: ideal victims of a neoliberal world order. And while the unhampered mobility of elite migrants (Bauman’s “travelers”) may give them the impression that nation-states are no longer a relevant unit in shaping their life trajectories, the vagabonds live in a world controlled by usually hostile state bureaucracies. In the age of neoliberal globalization, nation-states operate with extreme selectivity when it comes to allocating solidarity: they display utmost flexibility and generosity for some – the Business Class, usually – and act punitively and mercilessly towards others. If Kubota is intent on “critiquing how inequality is often solidified and intensified within multiplicity and fluidity” (2014: 4), she may want to take a closer look at this ambivalent and socially discriminating role of the nation-state, as well as at the patterns of social, often grassroots solidarity that attempt countering it (Blommaert 2013; 2015). An empirically unsustainable dichotomy between individualist hybridity and nation-state solidarity is not just intellectually but also politically of little use.

The thing is that – and I return to an earlier point – the elementary social fact of communication should disqualify any interpretation of “individualism” in our fields of study as rubbish. One cannot be understood in isolation, it takes someone else to ensure that we are understood as someone specific – here comes identity. And one can only be understood as someone when the process of understanding is directed by mutually ratified codes and norms – even momentary, fluid or ad-hoc ones – and situated in an appropriate social event allowing such a process. But this also means that “groups”, in actual social life, cannot be restricted to the “big” ones defined in the Durkheim-Parsons sociological tradition (and reified by statistical demography): we pass through a myriad of “groups” on a daily basis, and most of these groups are not experienced as groups – they’re just “people” we share the station platform, the cinema or the cafeteria with, or whose memes we retweet and “like”. The fact that we share a specific space with those people should put us on a trail of understanding what that sharing actually involves – and discover, so doing, that it’s actually quite a lot.

In our own field, Michael Silverstein (1998) introduced a highly useful distinction between “language communities” and “speech communities”. The distinction must be understood by reference to the dual laminated concept of language produced by language ideologies research. Language communities, Silverstein argued, were communities who subscribed to the Language-with-capital-L, the ideological object (say, “English”) we believe we “all speak”; speech communities, by contrast, were communities of people who effectively behave in ways that show sharedness of indexical (normative) codes and conventions. Where languages and groups are at stake, Kubota’s discussion is largely confined to “language communities”, and she shares that restriction with very many scholars in Applied Linguistics. The failure to distinguish between two separate forms of sociolinguistic groupness and their complex interactions (Silverstein 2014), again, leads to a failure to identify the precise forms of power and the precise loci of power (language communities typically being far more static, restrictive, regimented, institutionalized and coercive than speech communities). It also provokes a predictable conceptual fuzziness when “hybridity” is discussed – since such hybridity violates the one form of groupness conceivable in this field, the language community, it must be “individualistic”. While, of course, it can be all kinds of things but not an act of individualism, for it takes others to ratify someone as “hybrid”, and such “hybridity” only emerges as a counterpoint of established (“non-hybrid”) social norms and diacritics.

I believe it was Edward Sapir who already stated that there are far more groups than there are people. It is amazing to see how scholarship in our fields still appears to avoid the exploration of new forms of groupness, identity and solidarity, even if the explosive rise of social media and other mobile ICT’s has enabled people to shape forms of social life, of communities and networks unimaginable, of course, in the days of Durkheim and Parsons, with observably new and unpredictable modes of identity practice (Blommaert & Varis 2015). The “social” in “sociolinguistics” and “sociology” is being restructured as we speak, and the profound challenges to, for instance, the enduring legacy of structuralism in our sciences are both massive and inevitable. Yet, we seem to avoid the subject. For there is a risk that it might demonstrate that

- our traditional, and cherished, “thick” group identifiers of gender, class, ethnicity and so forth are actually shot through with all kinds of different, “light” but nontrivial and highly mobilizing forms of community membership in a way most of us seem to navigate quite unproblematically; and

- that all of us are, in fact, hybrid to the bone, even if we feel extraordinarily “mono”-this-and-that; that all of us have to be “hybrid” in the sense of being “integrated” in a multitude of different communities; and that few of us seem to be troubled, confused, lost or torn by that.

Both factors taken together, and taken seriously, will deny us the comfortable clarity of “group identities” we often assume in research, and take us into a messier field of analysis. Obviously, in this messier field some established simplistic analyses of power will be up for critical inspection as well – including, perhaps, even the Big Bad Ones: racism, sexism, ethnocentrism and … neoliberalism. But this messier field will offer, in return, far more accuracy and precision than the one we deserted.

The neoliberal conspiracy

Many of us, and this includes me, abhor the kind of social, political and economic order described by the term neoliberalism. And many of us regret its hegemonic position in our contemporary societies, and are convinced that something should be done about that. I believe, however, that quick-and-easy discussions of it, carried along by superficial and insufficiently precise evidence, are not useful. And facile, overdrawn accusations of “neoliberal complicity” extended to the work of people often involved in the detailed description of this neoliberal order serve only rhetorical in-group purposes. They do not advance our understanding of neoliberalism in any way and do not shape the intellectual tools we need in order to demystify it and dislodge its status as the contemporary doctrine of “normality”. Only a profound and rigorous engagement with neoliberalism will do, and such an engagement must accept an unpleasant truth: that neoliberalism has changed our societies, probably in an irreversible way; that a return to the pre-neoliberal order is probably impossible, and perhaps not even desirable. It must – and will – be followed by something different. And in the meantime, we need to adjust our intellectual tools and our focus of inquiry to these changing phenomena and processes, describe them meticulously and analyze them with the most demanding precision possible. The SSD approach grew out of exactly such an effort, and continues to develop rapidly and dynamically on that basis. I believe there are results that merit a serious debate, and deserve a lot better than what they get in most of the critical texts I read on SSD.

I said at the outset that I share many of the concerns voiced by Kubota and others; this was not just posturing. I have spent my academic life as well as my public and private life addressing inequalities, both at a macro-scale level and at the level of concrete cases, working invariably in what is usually called “the margins” – among those who systematically fall victim to the pressures of neoliberal globalization and governmentality. If today I advocate what I called here the SSD approach, it is certainly not out of naiveté or a lack of exposure to very many forms of injustice and inequality. It is out of a commitment to dig deeper into the mechanisms of injustice and inequality, to grasp the core of such mechanisms and to defend their victims. As I said above, within INCOLAS we have an outspoken preference for work in the “frontline” sectors of social struggle; none of us works on the “cosmopolitan, wealthy and privileged” people we have encountered in Kubota’s critique.[5] One may of course judge my own attempts in that direction to be misguided, silly or useless; but even so I really share the concerns of scholars such as Kubota. My comments are thus written with profound empathy, and with the desire to engage others in a dialogue in which serious attention is given to theoretical, methodological and empirical detail. I am tired of reading half-informed and less-than-half-reasoned critiques of what SSD actually is, does and stands for. Those who write such critiques should get tired of them as well.

The concerns voiced by Kubota are not new at all. In fact, they are old and worn out, certainly when their treatment triggers powerful déjà-vu effects for those who have been in the business for a while. It should be clear that the old modernist mantras, the static and stale theoretical assumptions and methodological blueprints have outlived their usefulness. For that reason, I am amazed when I read, once more, a critique of SSD or related developments in which the authors, at the end of their exercise, appear happy to withdraw back into the safety of modernist structuralism – the science doctrine that marked the era of colonialism. Contrary to popular belief that scientific postmodernism fuels neoliberalism, the same forms of modernist structuralism sustain the neoliberal scholarly imagination – just observe how the transition from “man, the social animal” as the consensus in the 1970s to “the selfish gene” as that of the 21st century was executed by means of one simple set of modernist-structuralist tools: statistics and experimental research, in the act also turning “scientific” into a synonym for “unrealistic”. Getting out of that corner, therefore, looks evident to me; but this involves a readiness to put everything back on the drawing board and risks being an unpleasant and taxing endeavor. In the meantime, let’s stop this nonsense about neoliberal conspiracies and scholars being complicit in them, either as creepy strategists or as naïve dummies. That, too, is unrealistic.

My own preference is: if you intend to destabilize a hegemony, try to understand it; don’t simply dismiss neoliberalism as a mirage or just another “political ideology”, but study it. Study the effects it has on the moral order that infuses the behavioral templates guiding people’s behavior and their appraisals and valuations of the behavior of others, and look for the cracks and fissures in that system – the small spaces of antagonism and agency-in-resistance that can provide empirical counter-arguments in analysis and building blocks for counter-activism. As scholars of communication, we should be uniquely equipped for that.

Postscript

Nelson Flores, in a recent article, adds to the cottage industry of uninformed and shallow criticism of sociolinguistic superdiversity. I and my colleagues are accused of:

three limitations of the super-diversity literature: (a) its ahistorical outlook; (b) its lack of attention to neoliberalism; and (c) its inadvertent reification of normative assumptions about language.

Most of the arguments developed above are entirely applicable here, so no new elaborate argument is required. Just speaking for myself, I invite the reader to apply Flores’ critique to the following works.

- Discourse: A Critical Introduction (2005) revolves around a theory of inequality based on mobile, historically loaded and configured communicative resources I call voice (following Hymes);

- Grassroots Literacy (2008) describes in great detail how and why two recent handwritten texts from Central Africa remained entirely unnoticed and unappreciated by their Western addressees. Literacy inequalities in a globalized world, thus, for reasons that have their roots in different histories of literacy in different places.

- The Sociolinguistics of Globalization (2010) addresses exactly the same phenomena: globalization expanding old inequalities while creating new ones due to a reshuffling of historically emergent linguistic markets, combined with a renewed emphasis on reified normativity by nation-state and other authorities.

In each of these books, the practical question guiding the theoretical effort, and significant amounts of data, is that of the systematic discrimination of large immigrant and refugee populations in Western countries such as mine. Ahistorical? Neoliberal? Reified normative assumptions about language?

This is n’importe quoi criticism in which the actual writings of the targets of criticism, strangely, appear to be of no material importance. And in which critics, consequently, repeat exactly what I said in my work, and then claim that I said the opposite.

One word about the “ahistorical” point in Flores’ criticism (and that of others). He equates “historical” with “diachronic”, a very widespread fallacy often seen as – yes, indeed – the core of an ahistorical perspective. “Historical” has to be “old”, in short, and whoever works on old stuff does historical work, while those who work on contemporary stuff are not historical in their approach. Since I work on issues in the here-and-now, I am “ahistorical”. Please read some Bloch, Ginzburg, Foucault or Braudel, ladies and gentlemen. Or some Bourdieu and Hymes, and even Gumperz and Silverstein: “historical” means that every human action, past and present, is seen as the outcome of historical – social, cultural and political – paths of development, and derives much of its function and effect from that historical trajectory. Which is what I emphasize systematically while working in the present. And find a lot of work on old stuff entirely ahistorical.

Further commentary in “defense” of what I am claimed to argue is a waste of time.

References

Agha, Asif (2007) Language and Social Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Arnaut, Karel, Jan Blommaert, Ben Rampton & Massimiliano Spotti (eds. 2016) Language and Superdiversity. New York: Routledge

Blommaert, Jan (2009) Language, asylum and the national order. Current Anthropology 50/4: 415-441.

—– (2013) Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters

—– (2015) Superdiversity old and new. Language and Communication 44: 82-88.

Blommaert, Jan & Piia Varis (2015) Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identies. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 139.

Kroskrity, Paul (ed. 2000) Regimes of Language. Santa Fe: SAR Press

Kroskrity, Paul, Bambi Schieffelin & Kathryn Woolard (eds 1998) Language Ideologies: Theory and Method. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kubota, Ryuko (2014) The multi/plural turn, postcolonial theory and neoliberal multiculturalism: Complicities and implications for Applied Linguistics. Applied Linguistics 2014: 1-22.

Moore, Robert (2013) ‘Taking up speech’ in an endangered language: Bilingual discourse in a heritage language classroom. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 69.

Rampton, Ben (1995) Crossing: Language and Ethnicity Among Adolescents. London: Longman

—– (2006) Language in Late Modernity: Interactions in an Urban School. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—– (2014) Gumperz and governmentality in the 21st century: Interaction, power and subjectivity. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 117.

Silverstein, Michael (1996) Monoglot ‘standard’ in America: Standardization and metaphors of linguistic hegemony. In Don Brenneis & Ronald Macaulay (eds) The Matrix of Language: 284-306. Boulder: Westview.

—– (1998) Contemporary transformations of local linguistic communities. Annual Review of Anthropology 27: 401-426.

—– (2003) Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language and Communication 23: 193-229.

—– (2014) How language communities intersect: Is “superdiversity” and incremental or a transformative condition? Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 107.

Silverstein, Michael & Greg Urban (eds. 1996) Natural Histories of Discourse. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Notes

[1] I must be emphatic: my comments start from sociolinguistics and not Applied Linguistics. I therefore have the advantage of not having to carry the burden of concerns – theoretical and practical – characterizing much of Applied Linguistics, it seems, and – I venture an interpretation – sometimes related to a degree of bad conscience about being in (or close to) the for-profit language industry. In my field, consequently, there is less unease about a possible tension between “theory” and “practice”. Most of what we do is to describe and explain.

[2] INCOLAS stands for the International Consortium for Language and Superdiversity. See, for information, this website.

[3] Kubota, like many others, appears to have an a priori negative appraisal of institutions and power as necessarily oppressive and “bad for people”. Foucault’s more sophisticated views of power-as-productive and institutions-as-enabling have not been taken on board.

[4] In that sense, and contrary to what Kubota writes, there is nothing “postmodern” about my view, since I reject modernism, which is of course not the same as Modernity. Like Zygmunt Bauman, who speaks of “liquid Modernity” and Scott Lash using “another Modernity”, I do not believe that Modernity has come to an end, but that it has transformed itself. I do believe therefore that classic-modernist frameworks for understanding the present stage of Modernity are hopelessly dated and that this conceptual anachronism constitutes one of the greatest problems of contemporary Modernity, and is one of its most prominent sources of injustice and inequality. See Blommaert (2009) for an illustration of the excluding powers of such dated frameworks.

[5] INCOLAS has made issues of security, policing and surveillance its programmatic priority, and the last INCOLAS meeting (London, Fall 2015) was entirely devoted to these matters. See Rampton (2014) and the introduction to Arnaut et al (2016).