Jan Blommaert

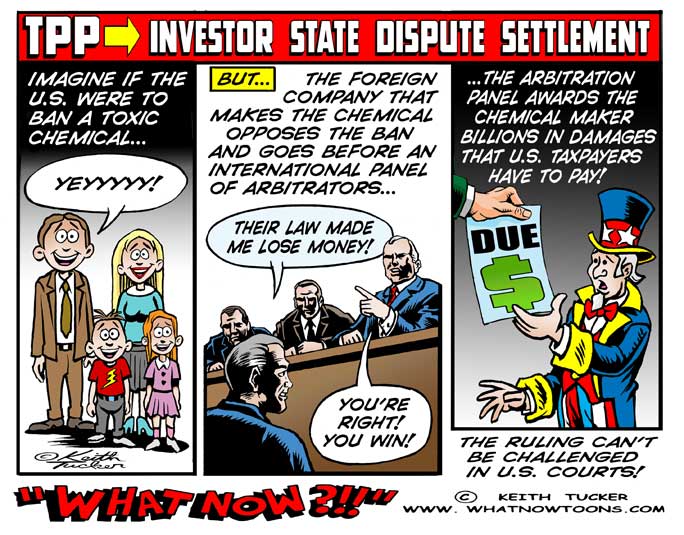

The negotiations between the EU and Canada about the CETA treaty have been stalled, initially by just two regional parliaments in Belgium, but gradually by a broader front of EU members, all of whom take exception to the Investment Court System (ICT), a specific variety of what has become knowm as ISDS – “Investor State Dispute Settlement”. The objections are not technical but profound – they revolve around a principle.

The principle was laid down a couple of centuries ago, as part of what we now call Enlightenment: it is the principle of equality under the law. Put simply, it implies that a Duke and a beggar must be subject to the same laws, be tried in the same way for the same crime, receive the same sanctions, enjoy the same rights and have access to the same legal instruments and procedures. It’s the very foundation of what has now, almost universally, been accepted as the democratic system of law and order.

Remarkably, ISDS is an exception to that. In the current ISDS systems, of the two parties involved – investors and states – only one of them has the right to initiate procedures. And that is the fatal flaw in the system.

Advocates of ISDS do have a point though: scale. They invoke economic globalization as the compelling reason why supranational jurisdictions are necessary. The logic is: transnational business and finance operate on the basis of a global strategy, and the scale level of nation-state legislation should not impede or disrupt the structure of such global manoeuvers. Hence ISDS, as an instrument to “correct” nation-state impediments and stay on track of the chosen business strategy.

It is not a bad argument; but it, once again, begs the question as to why an ISDS should not be built on the equality principle, recognizing that the nation-state scale level is also an obstacle for the other party in the game. Concretely: corporations have access to an international legal procedure when their global interests are endangered, but Volkswagen can only be prosecuted nationally for its software fraud, even if that fraud was a global phenomenon.

And a government cannot, for instance, internationally prosecute a corporation for the social and collateral costs of making thousands of its workers redundant in spite of very large profits made in that country (think of the worldwide reorganization announced by ING bank some weeks ago). Such actions, motivated by – exactly – the global corporate strategy, force governements to spend enormous amounts of cash in unemployment benefits, retraining and reskilling of laid-off workers, sometimes the reconversion and sanitation of abandoned industrial sites with severe and lasting ecological damage, and so forth – costs often weighing heavily on precarious national budgets for many years. And they are direct effects of economic globalization.

One can easily think of numerous other issues in which the weakness of the nation-state scale level as an actor in global economic processes is exploited by business and finance. The Panama Papers and Offshoreleaks brought shocking evidence of the complex systems of tax evasion deployed by business and finance corporations, all based, exactly, on movements of money, legal statuses and accounting practices from one country’s jurisdiction to another, keeping profits out of reach of the tax offices of the countries where they were earned. At present, very little can be done against it – the legal system of one country reaches its limits where that of another country starts. And within this fragmented world of jurisdictions, those forms of tax evasion are “not illegal”, as it is often repeated. But the scale of economic damage done in several parts of the world matches the scale of profit made from such practices of playing off these parts of the world against each other.

So why not take ISDS one step further, and recognize that the globalization of business and finance does indeed require an international jurisdiction, but a real one, one in which all parties have access to the same legal instruments. Why not think of an international court for economic crimes, modeled, perhaps, on the present International Court of Justice in The Hague – an idea which has been around for a while? It would add a quite commonsensical dimension lacking from the present ISDS system: that “Investor State Disputes” may have either one of both parties in either of the roles in the dispute – perpetrator as well as victim. And that true justice can only be done when this elementary principle is restored.

![]()