Jan Blommaert

1.

Michel Foucault’s course of lectures at the Collège de France in 1974-1975 was devoted to the theme of “Abnormal”. The edited version of these lectures offers one of the richest analyses of the genesis of the modern individual as an effect of power – a new system of power revolving around norms and enacted by a wide range of actors, from the Law through the family doctor to the family. In this new form of power, risk is the central given, and the body is the focus. The body is the seat of our instincts and, when out of control, may turn us (any and all of us) into a monster. The body, thus, becomes gradually “readable” as an index of character, of who you are. And families are charged, under the guise of “educating” their children”, with the care of the bodies of their children, who gradually should become people whose bodies are “healthy” and, hence, “normal”.

A catalyst for organizing this mode of power (a biopower governmentality) , Foucault argues, is the confession. Confessing becomes the archetype for one of the central tools of power: the “examination”, a regulated series of genres in which one has to speak the truth in the face of an authority, who will pass judgment over it. We have to confess to the police, the doctor, the psychiatrist, the priest, but also to the school teacher, our parents, and our peers. The confession, in that sense, becomes a step-up to one of the themes developed in Foucault’s latter courses: veridiction, the specific behavioral-discursive templates we have developed for “speaking the truth”. And the generalization of such forms of confession, adds Foucault, results in a “permanent autobiography” made up of small and big stories about ourselves, submitted to the normative judgment of others. And this permanent autobiography, thus constructed, is “who we are”: it is how we show ourselves to others within normative templates that can be recognizable as truthful.

2.

It is easy to see how Foucault’s observations about the confession, and modes of veridiction more generally, could resonate in the field of social media practices today. Much of what we are invited to do on social media, I propose, revolves around the construction of a “permanent autobiography” in Foucault’s sense: a sequence of small and big veridictional narratives by means of which we show ourselves to others as “true”, “real”, “authentic” and – derived from that – “likable”, “cool”, “attractive” or what not. Facebook’s “timeline” format provides a chronological linearity to updates – an iconic feature of “(auto)biography” – and “being yourself” is a key ideological precept there, as well as on other social media. Even if the formats and functions of Facebook are not the same as, say those on “professional” social media such as LinkedIn or dating apps such as Tinder, the normative expectation on each of them is that you are “yourself” and not hide behind a mask.

This, evidently, is the key element in confession: speak the truth, do it consistently and frequently, and do it in the presence of evaluating others. Others – note – will judge whether you are “true”, and it doesn’t suffice to believe that you’re “true” yourself. A “true” identity is interactionally, and normatively, constructed, around an imagined identity essence – “being yourself”. This essence is imagined singularly (and opposed to plural “masks” we have to wear in so many sites of life), while in reality it assumes very different shapes in different media. To make this clear: compare someone’s CV to that same person’s profile on a dating site, and ask which one would be judged as a “lie” by the person who constructed both. We are “ourselves” in a broad variety of actual forms and shapes (chronotopically organized, I would say), each of them experienced as “real” (even if not comprehensively so).

3.

This now takes us to social media as tools of governmentality. There is a burgeoning literature on social media as data-gathering tools serving interests alien to those animating the practices we perform on social media. Such interests include security as well as commerce, and they are fed by big data drawn from the activities performed on social media.

The quality of such data, naturally, heavily depends on the reliability of the information provided by users in their social media activities. And this is where the identity essentialism mentioned above enters the picture. The normative expectation informing social media interaction is, effectively, “veridictional”: since we wish to enter into specific types of relationships with others, we need to do so on a footing of credibility – the ways we show ourselves to others must trigger the indexicals of veridiction, converted into identity attributions that enable membership of groups and networks. And in view of that, we provide loads of stories feeding into such identity essentialism. Profile data – the basic stuff you have to provide for opening an account on social media – are a case in point.

These profile data are usually multimodal and contain images as well as text. Both are narrative modalities: they separately and jointly tell something about us, and are selected in such a way that we expect (or hope) others to recognize the relevance and authenticity of our stories. Let us turn to my own Twitter profile for an example.

The usual ingredients are there: (a) a profile picture, (b) a text on “who I am”, and (c) a banner illustration. The text (b) identifies me as “academic and knowledge activist”. This is how I want to address people from my Twitter account, and what I post there should reflect those “essential” identity feature. The relational appeal is: read my tweets as messages produced by an academic and knowledge activist. As for the two pictures (a) and (c), they directly connect to (b). In the profile picture (a), I am presented in my capacity of academic, lecturing in front of a screen showing lecturing slides. The banner illustration (c) is an (unclear) picture of me giving a speech at a trade union strike picket in Antwerp harbor a few years ago – here is the activist. The two “essential” identity features I offer to my followers on Twitter are mirrored in the pictures. Together they construct an autobiographical micro-narrative in which two moments of my life – a lecture and a speech during a strike – are invoked as evidence supporting the “truth” of who I am.

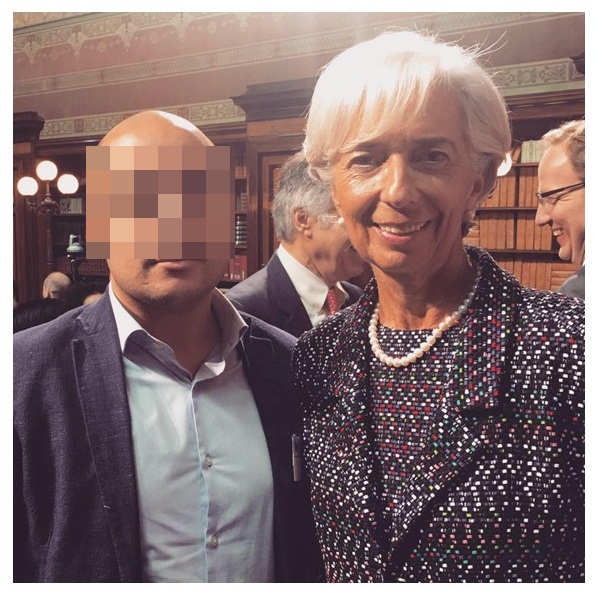

Much here, of course, is implicit and becomes readable through shared tacit indexical codes. Sometimes, people are more explicit though. The following profile picture displays a young aspiring Belgian politician next to Mrs Christine Lagarde (head of the IMF) – a “frame” in which the young man’s political ambitions are quite loudly stated by the presence of a global political celebrity. The autobiographical and veridictional nature of this picture is, I hope, entirely clear.

In both illustrations, the actual bodies are visible as part of the narrative. We can see Foucault’s moral “topography of the body” in the details: in my Twitter profile, for instance, I am dressed differently in both pictures – one kind of dress “typical” for academic lecturing, another more appropriate for early-morning trade union activism. My body posture, too, is different: the thoughtful lecturer versus the fiery activist. Both pictures, of course, were the outcome of a selection in which the “essence” (i.e. the “truthfulness”) of the identities I wished to convey was the benchmark.

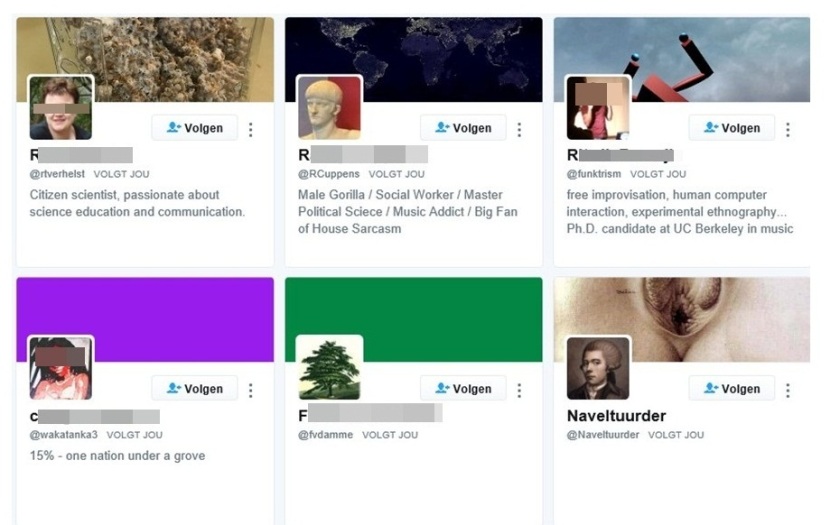

But even if bodies are not shown, similar “essences” can be expressed. Consider the Twitter profile images below, where people use “real” pictures (and names) as well as symbols, allegories, mottos and other items to identify themselves.

There is, thus, great semiotic diversity by means of which we produce such small stories about who we are, but the veridictional direction, I suggest, remains mandatory.

4.

Profiles such as the ones shown here, we can see, are small veridictional genres. They provide micro-narrative clues as to who we are, submitted to the normative judgment of others. The information contained in them, given its normative direction, is presented as “essential” – as the stuff you really have to know about me in order to enter into this particular relationship. As said above, it is this particular relationship that acts as a filter on what one releases in the way of information – hence the chronotopic differences between what we show in our CV, on Facebook, and on “professional” or dating sites.

It was Foucault’s massive contribution to theories of power that he showed how, in the power systems of Modernity, we ultimately police ourselves. The distributed and infinitely fractal nature of power (as normative regulation of everyday life) begins and ends with the modern individual him/herself, incorporating and enacting normative and evaluative expectations in every instance of social behavior. The norms we find “natural” ans “self-evident” as instruments for smooth social interaction (as Durkheim sketched them), Foucault insists, are at the core of the modern system of power.

The things documented here enter into interactions with protocols and algorithms designed by commercial organizations to produce sellable data on who we are and what it is we are after. Thus, when analyzing the more scary sides of social media usage, pointing towards the bad guys who collect such data on us and convert them into profiled formats by means of which our “bubbles” are created, doesn’t suffice, for we cannot exclude our own forms of agency from the equation. The system begins and ends with all of us, confessing regularly, frequently and consistently in a self-organized permanent autobiography, providing the perfect raw materials for highly sophisticated and infinitely detailed systems of power.