Jan Blommaert

(with ICD 2017)[1]

- Introduction

Online environments have become an integrated part of social reality ; as a new, huge and deeply fragmented infrastructure for social interaction and knowledge circulation, they add substantially to the complexity of social processes, notably those related to identity work and group formation.[2] We see, on the one hand, the emergence of online communities of unprecedented size – think of the population using Facebook, or of the huge numbers of players on some Massively Multiplayer Online Games. All of these have long been provoking questions about identity and social impact, often tending towards views of the destabilization of identity and of social cohesion (cf. e.g. De Meo et al 2014 ; Lee & Hoadley 2007). On the other hand we have the online emergence of strongly identity-emphasizing and highly cohesive “translocal micro-populations” (Maly & Varis 2015), and practices of online meaning making, control and circulation that betray the presence of at least widely shared systems of normative consensus and conviviality (Varis & Blommaert 2015; Tagg et al 2017; LaViolette 2017). Given the scope and scale of the online world, it is clear that we have barely started to scratch the surface, and in this paper I cannot claim to do more than that.

In what follows, I will venture into the less commonly visited fringes of the Web 2.0, in a space called the “Manosphere” (Nagle 2017). The Manosphere is a complex of (mostly US-based) websites and for a dedicated to what can alternatively be called “toxic masculinity” or “masculine victimhood”: men gather to exchange experiences and views on the oppressive role and position of women in their worlds, and often do so by means of ostensibly misogynist, sexist, (often) racist and (sometimes) violent discourse. The intriguing point is that the Manosphere, as an online zone of social activity, appears to be relatively isolated and enclosed. Large numbers of men are active on these online spaces, but there is no offline equivalent to it: no ‘regular’ mass movement of angry men organizing big marches, petitions and other forms of offline political campaigning. The Manosphere population is very much a group operating in the shadows of the Web (see Schoonen et al 2017; Smits et al 2017; Dijsselbloem et al 2017; Vivenzi et al 2017; Peeters et al 2017; Beekmans et al 2017).

There are moments, though, of public visibility, and I shall start from one such moment. In May 2014, a young man from California, Elliot Rodger, killed six people and injured fourteen others (before taking his own life) around the UCSB campus at Isla Vista, in what looked like one of many college shooting incidents (Langman 2016a). Rodger, the son of a Hollywood filmmaker, sent out a long manifesto by email just before his killing spree, entitled “My Twisted Life: The Story of Elliot Rodger” (see Kling 2017),[3] as well as several YouTube clips recorded prior to his actions.[4] Since Elliot mentioned Manosphere sites in the text, the manifesto offers us an opportunity to look closer into the ways in which such online infrastructures provide affordances for constructing an – admittedly eccentric – logic of action, strengthening Rodger’s sense of victimhood and providing rationalizations for the murders he committed during what he called his “Day of Retribution”. More in general, this exercise may lead us to a more precise understanding of the role played by popular online culture infrastructures in the construction of contemporary “outsider” identity templates, individual as well as collective ones (cf. Becker 1963; also Foucault 2003).

Drawing from Rodger’s manifesto, I shall first sketch the universe of communication in which he lived, focusing on how his online activities interacted with offline forms of interaction. This will offer us a tentative view of Rodger’s “culture”, characterized by a strong affinity with masculine victimhood and violence, which he shared with parts of the Manosphere. The latter operates, along with several other popular-cultural elements, as a learning environment in and through which, through “ludic” but quite serious practices, a logic of action is constructed.

- Elliot Rodger’s twisted world of communication

Herbert Blumer summarized one of the central insights in the tradition of Symbolic Interactionism as follows:

(…) social interaction is a process that forms human conduct instead of being merely a means or a setting for the expression or release of human conduct. (Blumer 1969: 8)

With this in mind, let us have a look at how Rodger’s manifesto informs us about the kinds of social interactions he maintained.

Born in 1991, Elliot Rodger was 22 when he took his own life and that of six others; he was a digital native, and he had a long history of mental disorder (Langman 2016b).[5] His parents and acquaintances described him as extremely withdrawn, and Rodger himself in his manifesto frequently described his “social anxiety” – an incapacity to adequately communicate in collective face-to-face situations, which he invariably experienced as extraordinarily stressful. Here is an example:

The class I started was a political science class. I figured I would gain some useful knowledge by taking it, though I disliked the teacher because he had the tendency to randomly call on me to answer questions. I was still terrified of speaking in front of the class, even if it was for one sentence. My social anxiety has always made my life so difficult, and no one ever understood it. I hated how everyone else seemed to have no anxiety at all. I was like a cripple compared to them. Their lives must be so much easier. Thankfully, there were no couples in this class, but I still had to see them when I walked through the school. The only thing I could do was keep my head down and pretend they didn’t exist. I still cried on the drive home every day.

This communicative disability leads to isolation, and this isolation quickly assumes a very specific shape. As an adolescent, Rodger develops a strong heterosexual desire, but girls do not appear to be attracted to him. Consequently, his problem of loneliness shifts towards something more specific and acute: a problem of involuntary celibacy which he experiences as torture. Since the girls he fancies do connect with young men (in Santa Barbara, especially men described by Rodger as “hunky”), couples become his object of resentment, and a sense of injustice is piled onto that of unhappiness:

As I spent a lot of time contemplating, I realized that my life was repeating itself in a vicious circle of torment and injustice. Each new semester of college yielded the same lonely celibate life, devoid of girls or any social interaction. It was as if there was a curse of misfortune placed upon me.

This injustice is acute, since Rodger imagines himself as superior to most other men of his age; he describes himself as “a perfect gentleman”, as good-looking, smart and generally attractive – which renders the fact that other men are more successful with girls outrageous:

How could an inferior, ugly black boy be able to get a white girl and not me? I am beautiful, and I am half white myself. I am descended from British aristocracy. He is descended from slaves. I deserve it more. I tried not to believe his foul words, but they were already said, and it was hard to erase from my mind. If this is actually true, if this ugly black filth was able to have sex with a blonde white girl at the age of thirteen while I’ve had to suffer virginity all my life, then this just proves how ridiculous the female gender is. They would give themselves to this filthy scum, but they reject ME? The injustice!

Rodger attempts to turn this outrageous state of affairs around by material improvements: fashionable and top-of-the range clothing, a BMW car (a present from his worried mother), and dreams of wealth. In order to realize the latter, he spends large sums playing on the Lottery:

This must be it! I was destined to be the winner of the highest lottery jackpot in existence. I knew right then and there that this jackpot was meant for me. Who else deserved such a victory? I had been through so much rejection, suffering, and injustice in my life, and this was to be my salvation. With my whole body filled with feverish hope, I spent $700 dollars on lottery tickets for this drawing. As I spent this money, I imagined all the amazing sex I would have with a beautiful model girlfriend I would have once I become a man of wealth.

When these desperate attempts to acquire a fortune fail, fantasies of violent retribution emerge, always triggered by seeing young couples who “steal” his happiness and are, in that sense, “criminals” who deserve to be severely punished:

I wanted to do horrible things to that couple. I wanted to inflict pain on all young couples. It was around this point in my life that I realized I was capable of doing such things. I would happily do such things. I was capable of killing them, and I wanted to. I wanted to kill them slowly, to strip the skins off their flesh. They deserve it. The males deserve it for taking the females away from me, and the females deserve it for choosing those males instead of me.

And a detailed script is constructed for the Day of Retribution:

After I have killed all of the sorority girls at the Alpha Phi House, I will quickly get into the SUV before the police arrive, assuming they would arrive within 3 minutes. I will then make my way to Del Playa, splattering as many of my enemies as I can with the SUV, and shooting anyone I don’t splatter. I can only imagine how sweet it will be to ram the SUV into all of those groups of popular young people who I’ve always witnessed walking right in the middle of the road as if they are better than everyone else. When they are writhing in pain, their bodies broken and dying after I splatter them, they will fully realize their crimes.

What is striking in Rodger’s manifesto is the paucity of offline, ‘normal’ communication he describes. As we have seen, he suffers from communicative anxiety whenever he is facing a group of interlocutors; but even one-on-one communication situations are often described as unsuccessful or unsatisfactory. But as mentioned earlier, he is a digital native, and frequent reference is made to online interactions in his manifesto. From early on, for instance, he is a dedicated player of the MMOG World of Warcraft (WoW), and playing that game provides him a (delicate and fragile) sense of community:

Upon setting up my new laptop, I immediately installed all of my WoW disks. I logged onto my account and took a look at all of my characters that I hadn’t touched for a year and a half. Right when I logged onto my main character, I was contacted by James, and he invited me to join an online group with him, Steve, and Mark. They all gave me a warm welcome back.

Changes in the nature of the WoW player community, however, make him decide to quit that game: too many “normal” people had joined WoW.

The game got bigger with every new expansion that was released, and as it got bigger, it brought in a vast amount of new players. I noticed that more and more “normal” people who had active and pleasurable social lives were starting to play the game, as the new changes catered to such a crowd. WoW no longer became a sanctuary where I could hide from the evils of the world, because the evils of the world had now followed me there. I saw people bragging online about their sexual experiences with girls… and they used the term “virgin” as an insult to people who were more immersed in the game than them. The insult stung, because it was true. Us virgins did tend to get more immersed in such things, because our real lives were lacking.

Other interactions with friends also proceed online, or are predicated upon prior online interactions:

During one of my frequent visits home in late Spring, I reunited with my old friends Philip and Addison. I hadn’t seen them since the night I emotionally cried in front of them at the Getty museum in the beginning of 2012. This reunion was sparked by the political and philosophic conversations I had been having with Addison over Facebook.

And Facebook also enables Rodger to keep tabs on his offline relations:

In November, my brief friendship with Andy, Stan, and their group faded away. I often saw on Facebook that they did things together without even inviting me, which is the same thing I’ve had to experience with other groups of friends that I’ve had in the past. I was always an outcast, even among people I knew. I grew tired of their lack of consideration for me, so I stopped calling them. They weren’t even popular anyway, and I wasn’t benefitting at all from their friendship. I still continued to meet with Andy at restaurants on occasion, however.

And then, of course, there is the Manosphere. Engaging with websites such as “PUAHate.com” (“Pick Up Artists hate”, taken down and renamed “Sluthate” after the Isla Vista killings) reassures Rodger that he isn’t the only one suffering from the cruelty of women:

The Spring of 2013 was also the time when I came across the website PUAHate.com. It is a forum full of men who are starved of sex, just like me. Many of them have their own theories of what women are attracted to, and many of them share my hatred of women, though unlike me they would be too cowardly to act on it. Reading the posts on that website only confirmed many of the theories I had about how wicked and degenerate women really are. Most of the people on that website have extremely stupid opinions that I found very frustrating, but I found a few to be quite insightful.

The website PUAHate is very depressing. It shows just how bleak and cruel the world is due of the evilness of women. I tried to show it to my parents, to give them some sort dose of reality as to why I am so miserable. They never understood why I am so miserable. They have always had the delusion that everything is going well for me, especially my father. When I sent the link of PUAHate.com to my parents, none of them even bothered to look at the posts on there.

Observe how Rodger describes the website as a place where a theory or worldview is constructed – an epistemic move towards generalization, from the particular and idiosyncratic to the systemic and common. And note that he considers this an important factor of understanding, valuable enough to be communicated to his parents. He had discovered a space where his own feelings, outlook and experiences were normal, even normative. And he wanted to communicate this to those who, in his eyes, systematically misunderstood him and defined him as an outsider. It is telling that, in the entire manifesto, the above fragment is the only one in which he attempts to share a resource for understanding his predicaments, with people from whom he genuinely expects support and sympathy.

- Sources and templates: the cultural material

Given what we have seen so far, it is safe to say that Rodger saw websites such as PUAHate.com as formative learning environments, places where he learned how to see his individual predicament fitted into a larger system, and where he learned how to respond to this systemic injustice (cf. Schoonen et al 2017). But apart from Manosphere sites and the World of Warcraft game he was passionate about, Rodger mentions several other sources of inspiration: he was quite deeply involved in particular forms of popular culture.

Remember that Rodger grew up in the Hollywood movie milieu; in his manifesto, he suggests that stars such as George Lucas were (at least) family acquaintances, and he proudly describes attending several red carpet premières of Hollywood blockbusters. His father was involved as a second unit director in the production of the 2012 hit movie The Hunger Games.[6] This genre of violent dystopian fantasy (to which WOW can also be added) clearly belonged to his range of strong interests, and he got addicted to A Game of Thrones as soon as he read it:

For the rest of the summer, I took it easy and played WoW with James, Steve, and Mark; just like old times. I also started reading a new book series called A Song of Ice and Fire, by George R.R. Martin. This medieval fantasy series was spectacular. The first book of the series was A Game of Thrones, and once I read the first chapter I just couldn’t put it down. It was like nothing I had ever read before, with a huge array of complex characters, a few of whom I could relate to. I found out that it was going to be adapted into an HBO television series, and I became very excited for that.

Delving into fantasy stories like WoW and Game of Thrones didn’t make me forget about all of my troubles in life, but they did give me a temporary and relieving sense of escape, which I need from time to time. Life would be impossible to handle without those temporary respites.

We can sense the powerful appeal of imagined universes characterized by violence, sex, ruthlessness and brutality in Rodger’s words here. Popular culture products such as these provided him with templates by means of which he could organize his experiences and conduct. The latter is made explicit by Rodger with respect to yet another source : a movie called Alpha Dog.[7]

The Santa Barbara plan was formed on that night, but its roots stretch all the way back to when I just turned eighteen. It was all because I watched that movie Alpha Dog. The movie had a profound effect on me, because it depicted lots of good looking young people enjoying pleasurable sex lives. I thought about it for many months afterward, and I constantly read about the story online. I found out that it took place in Santa Barbara, which prompted me to read about college life in Santa Barbara. I found out about Isla Vista, the small town adjacent to UCSB where all of the college students live and have parties. When I found out about all this, I had the desperate hope that if I moved to that town I would be able to live that life too. That was the life I wanted. A life of pleasure and sex.

In other words: the entire scenario of his Day of Retribution is modeled on a template Rodger largely derived from a violent movie. Popular culture proves to be a learning environment in the most immediate sense here.[8]

Of course, Rodger’s manifesto isn’t a log of his online activities and popular culture interests. The few items he explicitly mentions can be assumed to have particular importance in his constructed world, but there must be far more. There is, for instance, the powerful effect of the dramatic shooting at Columbine High School in 1999, perpetrated by teenagers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, which led not only to widespread outrage (voiced, among others, in Michael Moore’s award-winning documentary Bowling for Columbine),[9] but also to a video game called Super Columbine Massacre RPG (based on original surveillance camera images of the shootings),[10] and a number of copycat incidents in which perpetrators declared to be (or were later proven to have been) inspired by Harris and Klebold’s example. The Columbine massacre remains perhaps the most dramatic of the American school shootings, also because of its knock-on effects in other, similar incidents. It became, in effect, a template for similar actions.[11]

One such post-Columbine action, bearing striking similarities with that of Elliot Rodger, was the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007. On April 16 of that year, a student called Seung Hui Cho shot and killed 32 people. Interestingly, he, too, had posted videos prior to his actions, and he, too, left a manifesto: a collage of texts and images, articulating a sense of victimhood and a desire for (violent) retribution bearing striking similarities to that of Rodger. Consider the following fragment from Seung Hui Cho’s text:[12]

By destroying we create. We create the feelings in you of what it is like to be the victim, what it is like to be fucked and destroyed. Because of your annihilations, we create and raise new breeds of Children who will show you fuckers what you have done to us. Like Easter, it will be a day of rebirth. It will be a start of a revolution of the Children that you fucked. You have never felt a single ounce of pain your whole life, thus, by destroying you, by giving you pain, we attempt to show you responsibilities and meanings of other people’s lives.

Cho, like Rodger, expresses profound pain and bitterness over what he must have experienced as a life destroyed by the agency of others – who, because of that, deserved to die. Cho calls himself a victim, and Rodger concludes his manifesto with exactly the same qualifications:

All I ever wanted was to love women, and in turn to be loved by them back. Their behavior towards me has only earned my hatred, and rightfully so! I am the true victim in all of this. I am the good guy. Humanity struck at me first by condemning me to experience so much suffering. I didn’t ask for this. I didn’t want this. I didn’t start this war… I wasn’t the one who struck first… But I will finish it by striking back. I will punish everyone. And it will be beautiful. Finally, at long last, I can show the world my true worth.

The point to all this is that Rodger, in premeditating, preparing and executing his shooting, could draw on abundantly available cultural material for concrete and specific templates structuring his act. There is, as it were, a carefully elaborated aesthetics to the actions – see his “it will be beautiful” above. And in elaborating this aesthetics, Rodger draws on examples and models derived from earlier similar incidents as well as from the online and popular culture sources he intensely engaged with. All of this sources provide “logical” modes of action, patterns of argumentation and rationalizations that Rodger could invoke in designing his own actions.

- The aftermath: becoming cultural material

Elliot Rodger, as a digital native, not only consumed online popular culture, but as we have seen, he also created some. His manifesto was electronically circulated hours before his fatal drive into Isla Vista, and I already mentioned that he had uploaded several videos on YouTube as well. Both the manifesto and the videos are remarkable: the text is exceedingly well written and structured, and the videos appear to be well-rehearsed staged performances. Undoubtedly, Rodger’s exposure to the Hollywood professional in-crowd was formative.

Evidently, the Isla Vista shooting was headline news in the US, and several major TV networks controversially broadcasted fragments from Rodger’s YouTube videos, bringing material from the extreme fringes of the Web into mass circulation, and thus creating the raw materials for what we know as “memes” – a new and complex online popular culture genre in which (static or moving) image and message are blended in highly productive and diverse ways, often for no other apparent purpose than conveying “cool” conviviality in online communities (cf. Blommaert 2015; Varis & Blommaert 2015). A particular line from Rodger’s “Day of Retribution” video became emblematic in such memes: “I am the perfect gentleman”. Figure 1 illustrates this.

Figure 1: Elliot Rodger “Gentleman” meme. Source: https://me.me/i/th-elliot-rodgers-is-autistic-gentleman-supremacy-e-golden-mem-3683956 (20 November 2017)

Other memes poked fun of Rodger’s materialism and naiveté in dating girls,[13] and still others simply copied elements from Rodger’s manifesto and circulated it as a serious, instructional message, as in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Elliot Rodger text-quote meme. Source: https://onsizzle.com/t/elliot-rodger

(22 November 2017)

There is nothing exceptional to all this: memes can find their sources in nearly all and any event or aspect of life, so choosing a high-profile and heavily publicized incident as the object of memes is self-evident. The point is, however, that Rodger was directly influenced by specific sources and operated within existing templates when he committed his acts; but that he also became a format after the act. He and his killings became cultural material either providing legitimacy or rejecting his logic of action. In the present economies of knowledge and information, online infrastructures provide a colossal discursive overlay upon the more conventional news reporting.

Naturally, there was no shortage of uptake of the Isla Vista killings in the Manosphere, and this uptake was ambivalent. In discussions on Manosphere platforms, men condemned Rodger for being a “loser” while others praised him as a hero, as in Figure 3.

Figure 3: screenshot of Manosphere discussion on Elliot Rodger. Source: https://imgur.com/r/4chan/AET4cgb (20 November 2017)

The interesting thing, however, is how the figure of Elliot Rodger became entirely absorbed in the ideological structures of the Manosphere. One of these structures is sketched by Angela Nagle as follows:

“One of the dominant and consistent preoccupations running through the forum culture of the Manosphere is the idea of beta and alpha males. They discuss how women prefer alpha males and either cynically use or completely ignore beta males, by which they mean low-ranking males in the stark and vicious social hierarchy through which they interpret all human interaction.” (Nagle 2017: 89)

The Manosphere itself is split between alpha- and beta-male camps, and beta-males are usually encouraged either to turn themselves into alpha-males, or altogether reject (and possibly destroy) that world of male-female relationships (cf. Schoonen et al 2017; Vivenzi et al. 2017). The beta males, obviously, are the victims of a world in which women choose alpha males, and the label is shorthand for an entire system of rationalizations of unhappiness, involuntary celibacy, loneliness and revenge.

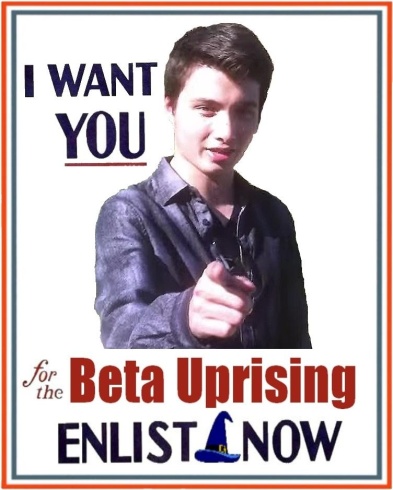

If we now return to Rodger’s manifesto using Nagle’s description of alpha and beta males, it is overly clear that Rodger self-identified as a beta male, a victim of a society in which women – way too independent and manipulating as they were, in his view – consistently ignored him in favor of more brutal, muscular and rugged types of (alpha) men. The latter, whom Rodger saw as stupid and naïve because they walked into the traps set out for them by women, also became his enemies, and eventually his victims during his Day of retribution. This act of uncompromising beta-masculine ideological rectitude turned Rodger into some kind of icon of the beta male camp, as we can see in Figure 4:

Figure 4: Elliot Rodger the beta male meme. Source: http://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1092353-beta-uprising (20 November 2017)

And within the Manosphere, he became a template of such till-death-do-us-part rectitude, important enough to have his acronym “ER” included in the glossary of Sluthate (the renamed successor of PUAHate.com).[14] Rodger’s figure indexes a radical, even extremist position which can be copied (as a template) by others. Smits et al (2017), for instance, describe the interactions of a man nicknamed “About2GoER” on Sluthate. The name signals intimate identification with “ER” (Elliot Rodger), and suggests a similar path of future action to that taken by “ER” (“about to go”). About2GoER “states that he rather wants to be with ‘slayers that are funny’ than ‘faggots that want the world to feel sorry for him’” (Smits et al. 2017) and is aggressive and extravagantly offensive, even by the quite impressive standards of Sluthate.

To sum up and conclude the analysis of the Elliot Rodger case: we have seen how his actions were “formatted”, so to speak, on the basis of sources and templates he had learned and developed in the online-offline world of the Manosphere, games and other forms of popular culture; and we have seen how his line of action, in turn, became part of the cultural material informing and providing action templates for others. Such templates provide a logic of action in which experiences, knowledge, feelings and aspirations are brought in line, so to speak, in a way that plausibly motivates specific lines of action. In the case of Rodger, the templates he had learned and developed converted loneliness and unhappiness into a strong and ideologically structured sense of victimhood – an identity of “victim”- which in turn, logically, motivated the extremely violent, destructive revenge on those whom he considered to be the perpetrators of the “crimes” that made him lonely and unhappy. We see here, in many ways, a classic instance of what Raymond Williams (1977) famously called “structures of feeling”: seemingly incoherent reactions and responses to experienced social realities that gradually become “structured” by ideological framings provided by similar feelings articulated by others. In the process, we witness the emerging of individual and collective identity categories (“victims”, “beta males”) and commonly ratified (“normal”) lines of action, which can now be ideologically rationalized as “the truth”. Rodger, in short, operated within the “culture” of the beta males – a culture of victimhood and resentment – and he took this cultural logic to its limits.

- Conclusion: the ludic formatting of online-offline social life

I now must take one step back, away from the concrete (and admittedly harrowing) case of Elliot Rodger, and explain how “outsiders” such as Rodger can inform us on more widespread social phenomena and processes. And we need to recall Blumer’s thesis, quoted earlier: what I have surveyed in the case of Rodger are, in essence, forms and patterns of social interaction forming human conduct, not just reflecting or expressing it. If we add George Herbert Mead’s view to this, such forms of interaction also form (not just reflect or express) who we are – our “minds”:

“We must regard mind, then, as arising and developing within the social process, within the empirical matrix of social interactions.” (Mead: 1934: 133)

In a slightly overstated rephrasing of Mead’s point, we could say that who and what people are is a residue of the totality of social interactions they engaged in over their lives, and specific aspects of who and what people are will be the residue of specific kinds of social interaction. Analytically, then, the crux of the matter is to understand the precise nature of these interactions. And this is where we need to engage with the peculiarities of the new online-offline communicative worlds we presently inhabit.[15]

We know a few things already – though not many. Identity work has acquired an outspoken level of fragmentation and mobility, something that can be imagined as “chronotopic”, in which different resources and normative behavior templates (“microhegemonies”) need to be deployed in specific TimeSpace configurations (cf Blommaert & Varis 2015). The elaborate identity repertoires needed for adequate levels of integration in this ever-expanding field of identity work requires permanent learning and re-learning work, and most online environments can be empirically described as “communities of knowledge”: chronotopes in which specific identity resources can be formed, learned and policed (cf. Blommaert 2018, chapter 4).

We also know that such communities – even if they operate as real communities, including forms of leadership and authority, normative behavioral scripts and levels of integration – are open, undemanding and flexible when it comes to membership, and that older conceptions of what it means to be a member impede a precise understanding of the actual forms of attachment developing between individuals and groups. The Manosphere is a case in point: even if men can be regular visitors and contributors to Manosphere forums, and attach great importance to interactions on these forums (as did, apparently, Elliot Rodger), the community does not have the robust and perennial structure of, say, a trade union or a sports team. As Smits et al (2017) showed, outspoken dissidence and even hostility are (even if grudgingly) tolerated, and as Vivenzi et al (2017) demonstrated, people can enter and leave as they wish.

So how do we imagine the specific forms of social interaction within such “light” communities of knowledge? Let us turn to a, perhaps, unexpected and counterintuitive (and rarely visited) corner of social thought.

In his classic Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga emphasized what he saw as an important counterpoint to Weber’s rationalization drive in Modernity: the playful character of many social, cultural and political practices. In our tendency to organize societies along rational management patterns, Huizinga insisted, we risked losing sight of the fact that much of what people do is governed by an irrational logic, a ludic pattern of action. Even more, much of what we see as the rational organization of societies is grounded, in fact, in play (Huizinga 2014: 5).

Huizinga (2014: 7-14) lists several features of “play”. I shall select a number of them.

- (i) Play is significant: it is a site of meaning-making in which “something is at play”;

- (ii) it is, at the same time a voluntary activity often experienced as a site of personal freedom;

- (iii) it is relatively unregulated and unconstrained by established rules and forms of control (distinguishing “play” from a “game” such as chess or poker);

- (iv) it is an authentic activity in which we observe the unconstrained “playing out” of the self; it outside the range of what is commonly seen as “useful” or “effective” (it is done “just for fun”);

- (v) it is enclosed in the sense that it often requires a particular spatiotemporal organization different from that of other activities; and finally,

- (vi) given all the previous characteristics, it is also a serious activity demanding focus, intensity and skill, and it has an inevitable aspect of learning to it.

Two remarks are in order. One, with respect to the characteristic of authenticity (iv above), it must be underscored that it is perfectly normal to play someone else while expressing some essential “self”. In fact, forms of play in which roles are assumed by players, masks or other garments are worn or names are being changed for the duration of the event are found everywhere. In the online world it suffices to think of highly developed communities such as those of cosplay and gaming to see the point; but think also of the widespread use of aliases or nicknames on social media platforms. Just as we can distinguish a Foucaultian “care of the self” in various forms of play, we see a “care of the selfie” in online play as well (cf Li & Blommaert 2017). In Rodger’s case, we saw plenty of such impersonations, and we saw plenty of hard work invested in the “care of the selfie”: the elaborate aesthetics of his manifesto and his videos, for instance.

Two, with respect to (v) above – Huizinga’s requirement of spatiotemporal “isolation” for play – we can emphasize the chronotopic nature of ludic practices. Play is often reserved for, and reliant upon, restricted and elaborately organized TimeSpace configurations. Think of a “play room”, “playground” or “play corner”, of “holiday” and “leisure” as segmented TimeSpace configurations reserved for ludic activities, but also of current expressions such as “quality time” or “me time” (a segment of time spent on ludic, non-work activities). Observe, by the way, the strong moral ring of such terms: they refer to things we absolutely need and value highly; denial of such things is often perceived as unacceptable. In online activities, the TimeSpace configuration is present as well, and relatively undemanding in addition: we need an individual and an online device, and little more is required. Which is why “spending time behind your computer” is often perceived as “asocial” or “individualistic”: we perceive an individual alone with his/her device, who is deeply involved, of course, with a community not sharing the physical TimeSpace but very much present and active in the “virtual” one. In Rodger’s case, we saw how the perception of offline social awkwardness bypassed his intense engagement with online and popular culture communities “below the radar”, including those of the Manosphere. And we saw the pervasive effect of these forms of separated, enclosed forms of involvement on his “mind” (to use the Meadian term here).

If we now take Huizinga’s characteristics and apply them to the “light” forms of membership in online communities, we see a potential for application – perhaps not to all forms of online membership but to many of them. We can see how attachment to online groups is not (in a great many instances) conditioned by permanent, heavily ordered, policed and “total” involvement – one does not have to become an expert in, say, advanced Barbecue techniques just by visiting Barbecue-focused websites or forums, and one does not have to participate in all events on a cosplay forum in order to be a “member”. One can also enter and participate on such online platforms without subscribing to the full range of norms, expectations and cultural premises prevailing there, and one can articulate one’s participation in terms of very different intentions and desired outcomes than the next person. An online gaming forum is not a school, even if we find organized and tightly observed learning practices on the online gaming forum too. It turns the gaming forum into a ludic learning environment in which different forms of knowledge practice are invited, allowed and ratified. Such practices – precisely – are “light” ones too – think of “phatic” expressions of attachments such as the retweet on Twitter and the “likes” on Facebook: knowledge practices not necessarily experienced as such, and rather more frequently seen as “just for fun”. And capable, in that sense, of generating “structures of feeling” shared among participants in the community.

But do note Huizinga’s final characteristic: ludic practice is serious practice. The relatively “light”, mobile and flexible features of online communities do not prevent intense and profoundly focused forms of attachment. The experience of freedom and authenticity, and the absence of obvious “normal” forms of usefulness and efficiency might, on the contrary, precisely contribute to the sometimes phenomenal investments made by members in their attachments to such groups. There is a degree of intimacy evolving from ludic practices (including the “phatic” ones just mentioned): people make friends while playing, because play enables them to show their “authentic” self, to show the “truth” about themselves.[16] Here, once more, are the “structures of feeling”: something is genuinely shared and constructed through such ludic forms of practice, and this sharedness is experienced as important and formative.

It is formative of strong normative templates, as we have seen in the case of Rodger. What he learned and developed in his online-offline enclosed communities of knowledge was a strongly normative (“normal”) sense of being and of action – a logic of action, as I called it earlier, or a “culture”. Rodger derived from his engagement in those communities an absolute certainty about his identity as a victim of a world that conspired to steal away his (sexually focused) happiness, and enough of a commitment to take this logic of action to its very end. And in so doing, he, in turn, contributed templates of thought, action and identity to other members of that community – his use of available formats contributed to a further solidification of these formats.

This is quite something in the way of social effect. Extreme cases of “outsiders” such as Elliot Rodger should alert us to the powerful “cultural” effects of the new online-offline worlds we inhabit, and for which, presently, we only have diminutive terms: “virtual” or “light” communities engaging in “playful” forms of attachment. The very lightness of these terms must encourage us to critically re-examine them, time and time again.

References

Appadurai, Arjun (1996) Modernity at Large : Cultural Consequences of Globalization. Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press.

Becker, Howard (1963) Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Beekmans, Inge, Anne-Marie Sweep, Linmin Zheng & Zhifang Yu (2017) Forgive me father, for I hate women. Diggit Magazine (in press).

Blommaert, Jan (2015) Meaning as a nonlinear effect: The birth of cool. AILA Review 28: 7-27.

Blommaert, Jan (2017) Ludic membership and orthopractic mobilization: On slacktivism and all that. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 193. https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/upload/6cfbdfee-2f05-40c6-9617-d6930a811edf_TPCS_193_Blommaert.pdf

Blommaert, Jan (2018) Durkheim and the Internet : Sociolinguistics and the Sociological Imagination. London : Bloomsbury.

Blommaert, Jan & Piia Varis (2015) Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 139. https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/upload/5c7b6e63-e661-4147-a1e9-ca881ca41664_TPCS_139_Blommaert-Varis.pdf

Blumer, Herbert (1969) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspectives and Method. Berkeley: University of California Press

Castells, Manuel (1996) The Rise of the Network Society. London : Blackwell

De Meo, Pasquale, Emilio Ferrara, Giacomo Fiumara & Alessandro Provetti (2014) On Facebook, Most ties are weak. Communications of the ACM 57/11 : 78-84.

Dijsselbloem, Jan, Ashna Coster, Boudewijn Henskens & Eva Veeneman (2017) Because of Patriarchy! Diggit Magazine (in press)

Foucault, Michel (2003) Abnormal. Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976. New York: Picador

Kling, Ben (2017) Elliot Rodger, Male Entitlement, and Pathologization. Medium, May 23, 2017. https://medium.com/@benkling/elliot-rodger-male-entitlement-and-pathologization-c394500309b3

Langman, Peter (2009) Why Kids Kill: Inside the Minds of School Shooters. New York: Macmillan.

Langman, Peter (2016a) Multi-Victim School Shootings in the United States: A Fifty-Year Review. https://schoolshooters.info/sites/default/files/fifty_year_review_1.1.pdf

Langman, Peter (2016b) Elliot Rodger: An analysis. https://schoolshooters.info/sites/default/files/rodger_analysis_2.0.pdf

Langman, Peter (2016c) Eric Harris: The search for justification. https://schoolshooters.info/sites/default/files/harris_search_for_justification_1.3.pdf

LaViolette, Jack (2017) Cyber-metapragmatics and alterity on reddit.com. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, paper 196. https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/upload/6614d6f8-3b03-4c8a-8ac9-b56ecf4b9cb1_TPCS_196_LaViolette.pdf

Lee, Joey J. & Christopher M. Hoadley (2007) Leveraging identity to make learning fun : Possible selves and experiential learning in Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs). Innovate : Journal of Online Education 3/6, article 5. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1081&context=innovate

Li Kunming & Jan Blommaert (2017) The care of the selfie: Ludic chronotopes of baifumei in online China. CRTL+ALT+DEM 22-11-2017. https://alternative-democracy-research.org/2017/11/22/the-care-of-the-selfie/

Maly, Ico & Piia Varis (2015) The 21st-century Hipster: On micro-populations in times of superdiversity. European Journal of Cultural Studies 19/6: 1-17

Mead, George Herbert (1934) Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nagle, Angela (2017) Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. London: Zero Books.

Peeters, Saskia, Natalia Wijayanti, Magan van Meer, Dennis de Clerck & Jonathan Raa (2017) The Threat of Toxic Masculinity: From Online Manosphere to Toxic Masculine Public Figures. Diggit Magazine (in press)

Schoonen, Maud, Hannah Fransen, Ruben Bastiaense & Norman Cai (2017) The Manosphere as a Learning Environment. Diggit Magazine (in press)

Smits, Laura, Meauraine van Gorp, Madelinde van der Jagt, Marissa Bakx & Noura Yacoubi (2017) Extreme Abnormals. Diggit Magazine. (in press)

Tagg, Caroline, Philip Seargeant & Amy Brown (2017) Taking Offense on Social Media: Conviviality and Communication on Facebook. London: Palgrave Pivot

Varis, Piia & Jan Blommaert (2015) Conviviality and collectives on social media: Virality, memes, and new social structures. Multilingual Margins 2/1: 31-45.

Vivenzi, Laura, William Schaffels, Gabriela De la Vega & Lennart Driessen (2017) Infiltrating the Manosphere: An Exploration of Male-Oriented Virtual Communities from the Inside. Diggit Magazine (in press).

Williams, Raymond (1977) Marxism and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Notes

[1] ICD 2017 is shorthand for the 2017 class in my “Individuals and Collectives in the Digital Age” course at Tilburg University, with whom I explored the issues documented in this text. I am deeply grateful to all of them: Marissa Backx, Ruben Bastiaanse, Inge Beekmans, Norman Cai, Ashna Coster, Dennis de Clerck, Gabriela De la Vega, Jan Dijsselbloem, Lennart Driessen, Hannah Fransen, Boudewijn Henskens, Daria Kholod, Thi Phuong Anh Nguyen, Dianne Parlevliet, Saskia Peters, Jonathan Raa, William Schaffels, Agotha Schnell, Maud Schoonen, Laura Smits, Eva Stein Veeneman, Anne-Marie Sweep, Madelinde van der Jagt, Meauraine van Gorp, Megan van Meer, Laura Vivenzi, Natalia Wijayanti , Noura Yacoubi, Zhifang Yu, Linming Zheng.

[2] This is the point of departure of Blommaert (2018), and this paper is part of the larger Durkheim and the Internet project. Evidently, the observation is not new, and I let myself be profoundly inspired by, among others, early visionary texts such as those of Castells (1996) and Appadurai (1996).

[3] The manifesto is an unnumbered 141-page document; in what follows, consequently, I cannot provide page number for the fragments I shall use. The full text is available in original form on https://medium.com/@benkling/elliot-rodger-male-entitlement-and-pathologization-c394500309b3. As we shall see further below, writing a manifesto is in itself part of a format for such forms of crime. Probably the most famous instance of the format was the 1515-page long 2083: A European declaration of Independence by Norwegian mass-murdered Anders Breivik, 2011. See https://publicintelligence.net/anders-behring-breiviks-complete-manifesto-2083-a-european-declaration-of-independence/

[4] Several of these clips can still be viewed on YouTube. His “Day of Retribution” clip can be viewed (with parental guidance) here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G-gQ3aAdhIo. See also Rodger’s profile on Criminal Minds Wiki: http://criminalminds.wikia.com/wiki/Elliot_Rodger

[5] See this excellent article for a detailed account of Elliot Rodger’s life: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/02/us/elliot-rodger-killings-in-california-followed-years-of-withdrawal.html

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Hunger_Games_(film)

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alpha_Dog

[8] Langman’s (2016a) review of half a century of college shootings in the US shows a dramatic increase of such incidents since the turn of the century, an era coinciding with the generalized introduction of the Internet as a household commodity. Harris and Klebold, we can note, were both active on online platforms in the peripheries of the Web. We cannot make categorical statements here, of course, but the Elliot Rodger case shows a direct influence of these new popular-cultural infrastructures on the formatting of his killing spree.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bowling_for_Columbine

[10] http://www.columbinegame.com/

[11] See Langman (2009; 2016c) for an analysis of Eric Harris’ motives and personality; Langman’s remarkable website contains original documents related to school shooters including Harris and Klebold, and it is helpful to look at the similarities across cases after the Columbine incident. A full analysis of these documents is beyond the scope of this paper. For a sober analysis of public multi-victim shootings in the Us, one can consult the FBI report examining incidents between 2003 and 2013: file:///C:/Users/c/Downloads/(U)_ActiveShooter021317_17B_WEB.PDF

[12] See https://schoolshooters.info/sites/default/files/cho_manifesto_1.1.pdf. On Criminal Minds Wiki, a clear parallel is drawn between Cho’s and Rodger’s shooting formats: http://criminalminds.wikia.com/wiki/Elliot_Rodger

[13] See for an example https://www.memecenter.com/fun/3276299/elliot-rodger-aka-jew-rich-boy-dating-simulator-2014

[14] See http://sluthate.com/w/Glossary#ER

[15] What follows is based on Blommaert (2017).

[16] This explains the very widespread genre of “confession” on social media. Confession, as Foucault (2003) observed, is a veridictional genre, a genre of truth-speaking in which an uninhibited self communicates fundamental truths to other uninhibited selves. Elliot Rodger’s manifesto and videos are, evidently, veridictional genres. And the density of “confessions” on the Manosphere is documented in Vivenzi et al (2017) and Beekmans et al (2017).